Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Associated with Udenafil

Article information

Abstract

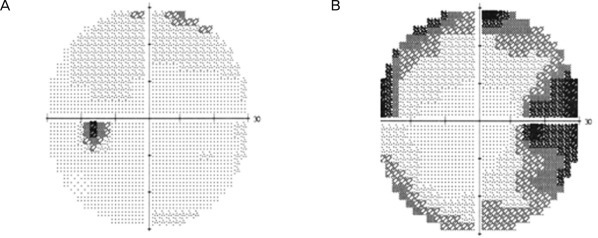

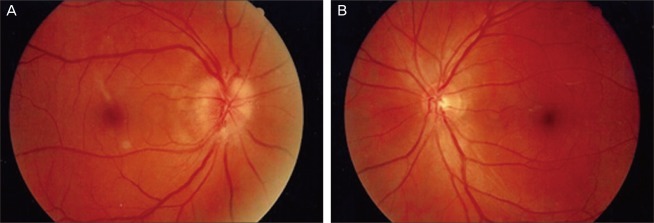

We report a case of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy associated with udenafil. A 54-year-old male presented with an acute onset visual field defect of the right eye after udenafil use. Examination revealed a relative afferent pupillary defect and a swollen disc. Automated visual fields revealed an enlarged blind spot and a narrowed visual field. Fluorescein angiography revealed both an inferior choroidal filling delay and an inferior sector filling delay of the optic disc in the arteriovenous phase as well as diffuse leakage of the optic disc in the late phase. Optical coherent tomography revealed increased thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer, especially in the area of the inferior disc. The patient was counseled to discontinue the use of udenafil and to monitor his blood pressure regularly. The disc swelling was resolved with residual optic atrophy one month after discontinuing the use of udenafil.

Udenafil (Zydena, Dong-A Phamaceutical, Seoul, Korea) is a drug used in urology to treat erectile dysfunction and belongs to a class of drugs called phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE 5) inhibitors. Other erectile dysfunction drugs such as sildenafil, tadalafil and vardenafil are also PDE5 inhibitors. The authors report the first literature case of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) associated with udenafil.

Case Report

A 54-year-old male complained of decreased visual field in his right eye. He also had a history of sexual dysfunction, for which he was prescribed udenafil. He took his first dose of 100 mg udenafil three days before his visit to our clinic. The next day he found that his eye was mildly irritated, and he had a mild headache. He discussed these symptoms with his urologist, and his symptoms subsided on their own after several hours. One day before his visit to our clinic, he took his second dose of udenafil. The following morning, approximately 12 hours later, he reported blurred vision and a decrease in the visual field of his right eye. This patient did have a 20-year history of smoking but no history of either hypertension or hypotension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, or cardiovascular disease. Upon examination, his best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20 / 25 in the right eye and 20 / 20 in the left eye. A pupillary examination revealed a right-sided relative afferent pupillary defect. Ocular motility was normal, and the biomicroscopy of the anterior segment was unremarkable. A dilated fundus examination of the right eye revealed prominent swelling of the disc with a disc rim hemorrhage (Fig. 1). Fundoscopy of the left eye revealed a healthy but crowded disc with a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.2 (Fig. 1). Fundus fluorescein angiography showed both an inferior choroidal filling delay and an inferior sector filling delay of the optic disc in the arteriovenous phase and diffuse leakage of the optic disc in the late phase (Fig. 2). Automated visual fields (Humphrey 30-2) revealed a generalized constriction of the visual field in the right eye and a normal visual field in the left eye (Fig. 3). Optical coherence tomography revealed a prominent thickening of the inferior retinal nerve fiber layer (Fig. 4). Laboratory testing revealed a normal blood count, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 10 and a normal CRP titer. A systemic evaluation was performed by a physician, and there was no evidence of cardiovascular disease, including hypertension, hypotension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. A neurologic examination was performed by a neurologist and was normal, and a magnetic resonance image (MRI) scan of the brain with gadolinium enhancement was able to demonstrate that the optic nerves appeared normal, and that there were no white matter lesions, which would have been suggestive of demyelinating disease.

(A) Fundus photograph of the right eye shows prominent swelling of the disc with a disc rim hemorrhage. (B) Fundus photograph of the left eye shows a healthy appearing but crowded disc with a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.2.

Fluorescein angiography shows an inferior choroidal filling delay and inferior sector filling delay of the optic disc in the arteriovenous phase (A) as well as diffuse leakage of the optic disc in the late phase (B).

Ocular coherence tomography shows prominent thickening of the retinal nerve fiber layer of the right eye. TEMP = temporal; SUP = superior; NAS = nasal; INF = inferior; OD = right eye; OS = left eye.

The patient was counseled to discontinue using udenafil and to regularly monitor his blood pressure. The patient's BCVA was improved to 20 / 20, and fundoscopy showed a slightly pale disc one month after he had discontinued the use of udenafil.

Discussion

AION is the most common acute optic neuropathy in people over the age of 50 [1]. The exact pathophysiology of AION remains unclear and is highly controversial. It is generally accepted that the site of the infarction is located in the retrolaminar portion of the optic nerve head, which is supplied by the short posterior ciliary arteries (SPCA), as this has been demonstrated histopathologically [2]. Doppler studies have also corroborated these findings by showing reduced blood flow in the SPCA [3]. The location of the impaired blood flow has been further refined by fluorescein and indocyanine green angiographic studies. These studies have demonstrated that delayed optic disc filling occurs without impairment of the choroidal circulation, which suggests that the vasculopathy is located in the para-optic branches of the SPCA after their branching from the choroidal branches rather than in the short ciliary arteries [4,5].

Hayreh et al. [6] have suggested that nocturnal hypotension may be an important precipitating factor in the pathophysiology of AION. This concept has been demonstrated by monitoring the ambulatory blood pressure over the course of 24 hours, which has shown that nocturnal hypotension may act as the final insult that leads to ischemia and AION in optic nerves that have been previously rendered vulnerable to ischemia by predisposing factors.

Beck et al. [7] have also noted that some discs have certain anatomic features that seem to predispose them to AION. Burde [8] has coined the term "disc at risk" to describe these structurally crowded discs, which are characterized by a small nerve head with a small or absent physiologic cup, abnormal branching of the central vessels, and full nerve fiber bundles that obscure the disc margin.

During sexual stimulation, the cavernous nerves release nitric oxide, which induces cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) formation and leads to smooth muscle relaxation and increased blood flow to the corpus cavernosum. This results in an erection. PDE5 is a naturally occurring enzyme that is found in high concentrations in the corporis cavernosum and that breaks down cGMP. Sildenafil citrate selectively inhibits PDE5, thus blocking the breakdown of cGMP and facilitating the erectile process [9].

It is hypothesized that the mild hypotensive effect of PDE5 inhibitors accentuate physiological nocturnal hypotension, which may result in ischemia of the optic nerve head and compartment syndrome in a susceptible disc [10]. An alternative explanation is that these medications reduce optic nerve head perfusion or disrupt the ability to autoregulate due to the potentiation of nitric oxide [10].

There have been several case reports that have described AION in users of PDE5 inhibitors. Egan and Pomeranz [11] have reported on sildenafil-associated AION, and Cunningham and Smith [12] have also reported a case of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy associated with sildenafil (Viagra; Pfizer, New York, NY, USA). Bollinger and Lee [13] have reported a recurrent visual field defect and ischemic optic neuropathy associated with tadalafil rechallenge. There have been no published case reports that have linked an episode of AION to udenafil.

The commonly associated systemic diseases include arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, hyperlipidemia, cerebrovascular accidents, and arteriosclerosis [14]. Various associated systemic diseases may interfere with the autoregulation of blood flow in the optic nerve head and make the optic nerve head vulnerable to AION. Lee et al. [15] have reported that hypertension, high cholesterol and decreased cup-to-disc ratio were observed in more than 60% of Korean patients with AION and thereby defined these as major risk factors.

Chung et al. [16] have reported that, of the 137 patients identified with AION in their study, the 28 smokers were statistically younger, with a mean age of 51 years, than the 83 nonsmokers, who had a mean age of 64 years. They concluded that cigarette smoking is an important risk factor in the development of AION, and that the cessation of smoking appears to reduce the risk of AION to that of the nonsmoking population. Lee et al. [15] have also reported that, of the 48 patients with AION in their study, the mean age of the nine smokers, was less than the 50.5 years of the nonsmokers. Of the nine smokers, four had smoking history as the only risk factor for AION. The authors also suggested that smoking is an important risk factor of AION and may be the only risk factor in younger patients.

The differential diagnosis of AION included functional visual loss, retinopathy (hypertensive retinopathy, central serous retinopathy, congenital maculopathy, pigmentary reitnaopathy, amelanotic melanoma, and cellophane maculopathy), amblyopia, glaucoma, keratoconus, pseudopapilledema, miscorrected refractive error, Leber's congenital amaurosis, and cortical visual loss [16].

Although the funduscopic image and fundus fluorescein angiography were most consistent with AION, the possibility of inflammatory optic neuropathy (optic neuritis) was also considered. Laboratory testing revealed no evidence of systemic inflammation. The neurologic examination was also normal, and the MRI scan of the brain with gadolinium enhancement demonstrated that the optic nerves appeared normal, and the lack of white matter lesions were not suggestive of demyelinating disease.

The actual duration of the pharmacologic effect of udenafil is approximately 24 hours. Patients are told to take udenafil approximately 90 to 120 minutes prior to sexual intercourse. Since the patient in this case study took the udenafil at night and then fell asleep after sexual intercourse, he noticed the visual field defect the following morning. We believe that udenafil may have contributed to the episode of AION in this patient. The risk factors of this patient were a decreased cup-to-disc ratio and a smoking history. The udenafil may have sufficiently accentuated his physiologic nocturnal hypotension to decrease the perfusion pressure in the posterior ciliary arteries. This may have resulted in ischemia of the disc that was already predisposed to AION due to the anatomic disc-at-risk configuration. The temporal relationship between the dose of udenafil and the onset of visual field defect make it difficult to accept the notion that these were unrelated coincidental events.

During the evaluation of patients with signs and symptoms of AION, a complete review of medications, including questions about udenafil use, is essential. Patients may be reluctant to inform their doctors about their use of udenafil as a result of the stigma that is associated with erectile dysfunction.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.