|

|

| Korean J Ophthalmol > Volume 27(5); 2013 > Article |

Abstract

We report two cases of surgical removal of a retained subfoveal perfluorocarbon liquid (PFCL) bubble through a therapeutic macular hole combined with intravitreal PFCL injection and gas tamponade. Two patients underwent pars plana vitrectomy with PFCL injection for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. In both cases, a retained subfoveal PFCL bubble was noticed postoperatively by funduscopy and optical coherence tomography. Both patients underwent surgical removal of the subfoveal PFCL through a therapeutic macular hole and gas tamponade. The therapeutic macular holes were completely closed by gas tamponade and the procedure yielded a good visual outcome (best-corrected visual acuity of 20 / 40 in both cases). In one case, additional intravitreal PFCL injection onto the macula reduced the size of the therapeutic macular hole and preserved the retinal structures in the macula. Surgical removal of a retained subfoveal PFCL bubble through a therapeutic macular hole combined with intravitreal PFCL injection and gas tamponade provides an effective treatment option.

Subretinal perfluorocarbon liquid (PFCL) retention has been reported to occur following vitreoretinal surgery using PFCL in 0.9% to 11.1% of cases [1,2]. Subfoveal PFCL retention has been reported to be associated with poor visual outcome because of its potential direct toxic effects on the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and photoreceptor cells [3,4]. Most surgeons agree with the need to remove retained subfoveal PFCL surgically [4-6]. However, although several techniques for the removal of subfoveal PFCL bubbles have been described [5-9], no standard treatment method has been established. Attempted pneumodisplacement by injecting intravitreal gas has been unsuccessful [5]. Direct surgical aspiration via a juxtafoveal retinotomy site adjacent to the retained PFCL bubble has been attempted with variable results [5,6,8,9]. However, this procedure can cause vision-threatening complications, such as macular hole, submacular hemorrhage, enlargement of the juxtafoveal retinotomy, or macular photoreceptor or RPE damage [6]. Because of these potential complications, temporary therapeutic retinal detachment to displace retained subfoveal PFCL was introduced [7]. The authors describe two patients who underwent surgical removal of subfoveal PFCL through a therapeutic macular hole and gas tamponade.

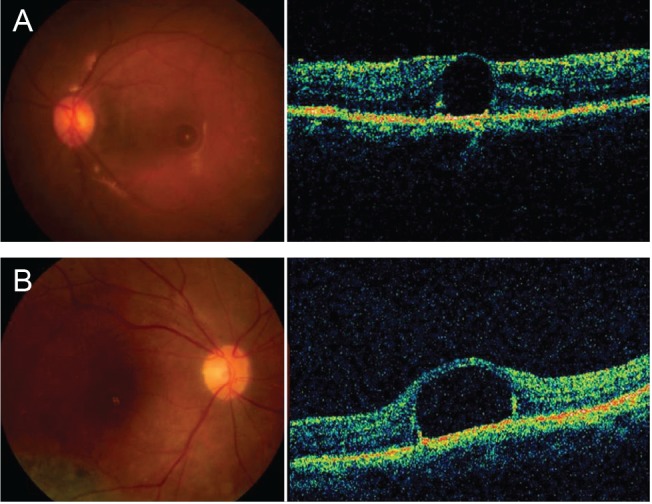

A 67-year-old woman with loss of visual acuity in the left eye for 2 days was referred to our hospital. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in the left eye was hand motion. Fundus examination revealed a supero-temporal bullous macula-off retinal detachment with one peripheral retinal tear at the 3-o'clock direction. The patient underwent 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy assisted by PFCL (perfluoro-n-octane; Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) injection, laser treatment around the retinal tear and peripheral lattice degeneration, and PFCL-air exchange, followed by silicone oil injection. Two days later, subfoveal PFCL retention was noticed by funduscopy and optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Fig. 1A). It is of note that the retina overlying the PFCL was extremely thin.

A 66-year-old woman with recurred rhegmatogenous retinal detachment of the right eye was referred to our hospital. The patient had a one-month history of scleral buckling, cataract operation, and pars plana vitrectomy with intravitreal gas injection in the right eye. Visual acuity of the right eye was limited to 20 / 200. A fundus examination revealed inferotemporal retinal detachment with multiple peripheral retinal tears at 10 o'clock complicated by proliferative vitreoretinopathy. She underwent two additional vitrectomies using PFCL, and reattachment of retina was achieved. Three months after the last surgery, however, a subfoveal PFCL bubble was found by funduscopy and OCT (Fig. 1B), and visual acuity of the right eye was limited to 20 / 1,000.

In case 1, we attempted to remove the subfoveal PFCL 2 days after the first surgery using the method described by Le Tien et al. [7], which involves therapeutic retinal detachment involving the macula using a subretinal fluid injection and displacement of the subfoveal PFCL by applying a sitting position. Therapeutic retinal detachment was induced by slowly injecting balanced salt solution through a retinotomy using a subretinal needle (Fig. 2A). However, before the therapeutic retinal detachment reached the macula, a half-disc-diameter-sized macular hole spontaneously developed, and the PFCL bubble popped up through the macula hole (Fig. 2B). The patient underwent laser treatment around the retinotomy site, followed by 18% sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) tamponade. She was instructed to maintain a prone position for one week.

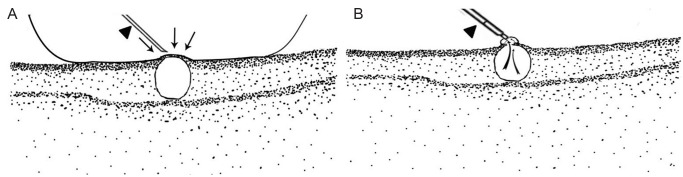

In case 2, after the experience of the case 1, removal of the subfoveal PFCL through a planned therapeutic macular hole was attempted. Briefly, additional PFCL (perfluoro-n-octane, Alcon) was injected to cover the posterior portion of the eyeball to prevent abrupt expulsion of the subfoveal PFCL and to minimize the size of the therapeutic macular hole (Fig. 3A). Retinotomy was performed on the thinnest point of retina overlying the subfoveal PFCL bubble, which was confirmed by preoperative OCT using the bent tip of a 23-gauge machinery vapor recompressor blade (Fig. 3A). The subfoveal PFCL was removed through the therapeutic macular hole using a silicone-tipped backflush needle (Fig. 3B). After gas tamponade (SF6), we instructed the patient to maintain a prone position for one week.

Two weeks after surgery, the subfoveal PFCL bubbles and macular holes had disappeared in both cases. Fundus photography and time-domain OCT taken two weeks after PFCL removal showed well-preserved retinal structures (Fig. 4A and 4B). Three months after the surgical removal of the subfoveal PFCL, BCVA improved to 20 / 40 in both cases. In case 2, at one year after subfoveal PFCL removal, spectral domain-OCT (Spectralis OCT; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) revealed relatively well-preserved retinal structures even after additional vitrectomy due to recurred retinal detachment after PFCL removal (Fig. 4C).

In both of our cases, the therapeutic macular hole was completely closed and good visual outcomes were achieved, which we attributed to the short durations of the presence of the macular holes. The better preservation of retinal structures in case 2 might be due to the small size of the therapeutic macular hole, which was possible due to the additional intravitreal PFCL injection.

We believe that our surgical method has several advantages. First, when the extremely thin retinal tissue overlying the PFCL bubble was incised, almost no tissue injury or loss occurred. An additional injection of preretinal PFCL could minimize the size of the macular hole and facilitate gentle aspiration of subretinal PFCL. Second, as we did not induce retinal detachment in the macula, no additional damage to perifoveal photoreceptors occurred during surgery. Third, this method is very easy to perform and requires no subretinal instruments.

However, the necessity of the prone position, which is uncomfortable to patients, is a limitation of our surgical procedure. Gas tamponade also has potential complications, such as intraocular pressure elevation and delayed visual restoration. Further study of a greater number of patients is warranted to compare the surgical and visual outcomes of treatment methods.

We conclude that the removal of subfoveal PFCL using additional intravitreal PFCL injection and a therapeutic macular hole followed by gas tamponade could be an effective and safe treatment method for a retained subfoveal PFCL bubble.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital Research Fund (grant no. 11-2009).

REFERENCES

1. Bourke RD, Simpson RN, Cooling RJ, Sparrow JR. The stability of perfluoro-N-octane during vitreoretinal procedures. Arch Ophthalmol 1996;114:537-544.

2. Garcia-Valenzuela E, Ito Y, Abrams GW. Risk factors for retention of subretinal perfluorocarbon liquid in vitreoretinal surgery. Retina 2004;24:746-752.

3. Berglin L, Ren J, Algvere PV. Retinal detachment and degeneration in response to subretinal perfluorodecalin in rabbit eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1993;231:233-237.

4. Lee GA, Finnegan SJ, Bourke RD. Subretinal perfluorodecalin toxicity. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1998;26:57-60.

5. Lai JC, Postel EA, McCuen BW 2nd. Recovery of visual function after removal of chronic subfoveal perfluorocarbon liquid. Retina 2003;23:868-870.

7. Le Tien V, Pierre-Kahn V, Azan F, et al. Displacement of retained subfoveal perfluorocarbon liquid after vitreoretinal surgery. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:98-101.

Fig.┬Ā1

Preoperative fundus photography (left) and macular optical coherence tomography (right). (A) Case 1. (B) Case 2. Retained subfoveal perfluorocarbon liquid is shown in both cases.

Fig.┬Ā2

Intraoperative photographs of case 1. (A) Therapeutic retinal detachment was induced by injecting fluid through a retinotomy. (B) The perfluorocarbon liquid (PFCL) bubble (arrow head) popped up through a spontaneous macular hole (arrow). The dashed line indicates the margin of the therapeutic retinal detachment. We removed the subfoveal PFCL bubble and filled the eyeball with gas.

Fig.┬Ā3

Schematic drawings of the surgical technique performed in case 2. (A) Additional perfluorocarbon liquid (PFCL) was injected intravitreally to cover the posterior portion of the eyeball and to prevent abrupt PFCL expulsion through a macular hole (arrow). Retinotomy at the extremely thin retinal tissue just overlying the subfoveal PFCL bubble was created using the bent tip of a 23-gauge blade (arrowhead). (B) Subfoveal PFCL (bent arrow) was removed along with the intravitreal PFCL using a silicone-tipped backflush needle (arrowhead).

Fig.┬Ā4

Fundus photograph (left) and macular optical coherence tomography (right) 2 weeks after surgery. (A) Case 1. (B) Case 2. Note that the subfoveal perfluorocarbon liquid (PFCL) bubbles and macular holes disappeared in both cases and that the retinal structures were better persevered in case 2. (C) Follow-up spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of case 2 at 1 year after PFCL removal shows the well-preserved retinal structures in the macula.

- TOOLS

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print