Acute Bilateral Visual Loss Related to Orthostatic Hypotension

Article information

Abstract

A 50-year-old man had undergone lumbar vertebral surgery and was confined to bed in the supine position for three months. When he sat up from the prolonged supine position, he showed clinical signs of orthostatic hypotension and reported decreased vision in both eyes. He also had underlying anemia. Ophthalmologic findings suggested bilateral anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (ION) as the cause of the visual loss. Although there are numerous reports of ION in the setting of hemodynamic compromise, such as systemic hypotension, cases of ION-associated orthostatic hypotension are very rare.

Ischemic optic neuropathy (ION) may develop in settings of hemodynamic compromise, such as systemic hypotension, blood loss and anemia [1,2]. Perioperative ION is a subgroup of ION and is associated with perioperative hypotension and anemia [3]. Another well known ION related to hypotension is "uremic optic neuropathy" that presents in patients with chronic renal failure and dialysis [4-6].

Prolonged immobilization of the body has extensive deleterious physiologic consequences. After a long period of immobilization, there is a marked pooling of blood in the lower extremities causing a decrease in the circulating blood volume. This causes orthostatic hypotension, if an individual attempts to sit or stand, depleting the brain of blood and oxygen and often leading to fainting [7].

We report an individual who developed acute bilateral visual loss with optic disc edema after standing up from a prolonged bed-ridden position. We believe it to be a case of ION related to orthostatic hypotension.

Case Report

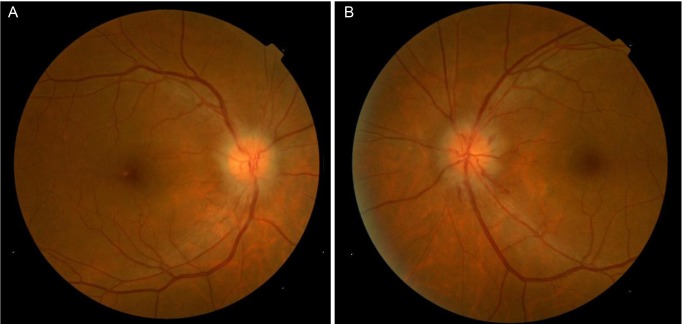

A 50-year-old man was referred to us due to decreased visual acuity in both eyes. The patient had spondylolisthesis and had undergone a lumbar laminectomy three months prior to these symptoms. After the operation, he had been bed-ridden in the supine position. The day before the visit, the patient had sat up for the first time and experienced momentary dizziness, nausea and facial pallor. Blood pressure decreased from 135 / 85 mmHg to 90 / 60 mmHg. A few hours later, the patient complained of blurred vision in both eyes. The next day, we measured a best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 0.3 in both eyes. The pupillary light reflex was decreased in both eyes. Fundus examination revealed optic disc edema in both eyes and a peripapillary flame-shaped hemorrhage in the left eye (Fig. 1). The Humphrey visual field test demonstrated generally decreased sensitivity in both eyes. Fluorescein angiography showed definite delayed dye filling of both of the optic discs. Contrast-enhanced orbital magnetic resonance imaging did not show remarkable findings, and there was no retrobulbar pain. The patient had iron deficiency anemia, and his hemoglobin level was 10.5 g/dL. He also had benign prostate hypertrophy and was prescribed tamsulosin (0.2 mg daily). Systemic evaluations including laboratory and cardiovascular work-up showed no other abnormal findings. The cardiovascular work-up included echocardiogram and magnetic resonance angiography of the carotid arteries. Methylprednisolone pulse therapy was initiated. However, the next day, vision in the right eye further decreased to 0.05. Vision stabilized for the next 10 days. Two weeks after the initial visit, fluorescein angiography showed improved dye filling on both optic discs. However, improvement was not complete in the right optic disc (Fig. 2). Vision slowly improved and, after six months, BCVA was 0.4 and 0.6 in the right and left eyes, respectively. Both optic discs were pale, and retinal nerve fiber layer thinning was prominent (Fig. 3). The visual field remained severely constricted.

Fundus photograph indicating features of optic disc edema in both eyes (A,B) and peripapillary flame-shaped hemorrhage in the left eye (B).

Fluorescein angiography on the day of initial visit (A,C) and two weeks later (B,D). (A) Venous phase demonstrating definite delayed dye filling on the right optic disc. (B) Arterio-venous phase two weeks later showing improved filling on the right optic disc. (C) Venous phase showing delayed dye filling on the left optic disc. (D) Venous phase two weeks later showing improved filling on the left optic disc.

(A) Optic nerve disc edema in both eyes and peripapillary flame-shaped hemorrhage in the left eye were resolved. Both optic discs showed temporal pallor after six months of decreased vision. (B) Optical coherence tomography demonstrating prominent thinning in the retinal nerve fiber layer in both eyes six months after the initial event. TEMP = temporal; SUP = superior; NAS = nasal; INF = inferior.

Discussion

More than 300 cases of ION induced by shock have been reported and have established a firm link between hypotension and ION [1,2]. ION related to hypotension is most often observed in patients with chronic renal failure and on dialysis [4]. Haider et al. [5] observed four cases of anterior ION in a series of 60 patients undergoing dialysis over a two-year follow-up. Hypotension was acute and temporary and associated with the dialysis procedure. Most patients were also chronically anemic. Servilla and Groggel [8] reported a case of typical anterior ION in a uremic patient, which occurred following an acute hypotensive episode during hemodialysis. Jackson et al. [9], Michaelson et al. [10], and Basile et al. [11] also reported cases believed to be secondary to a hypotensive episode. Several cases of anterior ION resulting from rapid correction of malignant hypertension have also been reported [12-14]. The pathogenesis of anterior ION that occurs in this setting is likely to be related to impaired autoregulation of the vessels supplying the optic nerve head and to the reduction in perfusion pressure, leading to ischemia [4]. There are numerous reports of ION associated with spontaneous or traumatic blood loss [1,2,15,16]. Visual loss was usually bilateral in the reported cases. About 50% of patients experienced some recovery of vision, and 10% to 15% of patients recovered completely. Hayreh [1] reported that there is typically a time delay of up to 10 days between bleeding and the onset of visual loss. Cases of perioperative ION are examples of ION associated with hemodynamic compromise. Most of the cases have bilateral simultaneous involvement. Pathogenesis is believed be associated with perioperative hypotension and anemia [3].

Cases of ION induced by orthostatic hypotension are rare. We found only one case in MEDLINE. Connolly et al. [17] reported a case of anterior ION induced by a repeated episode of orthostatic hypotension in patients who underwent simultaneous transplantation of the pancreas and kidney.

Painless acute visual loss accompanying optic edema is a characteristic clinical presentation of anterior ION. Bilateral presentation is unusual in ION, although it is a typical feature of ION in the setting of hemodynamic compromise [4]. Optic disc filling delay on fluorescein angiography is a common feature of non-arteritic anterior ION [18], and it is not a feature of non-ischemic optic disc edema [19]. In the present case, optic disc filling delay was definite in both eyes at the acute stage, and the filling delay had improved two weeks later. This observation gives strong evidence of ischemic optic disc edema. The substantial recovery of visual acuity in the presenting case is not a typical feature of ordinary anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION). However, this is common phenomenon in cases of ION associated with hemorrhage. Many authors also have reported substantial visual improvement in cases of ION related to hypotension [6,14,17,20]. They have postulated that volume replacement, correction of uremia with dialysis, or corticosteroid therapy might have been effective for vision recovery. These reports, however, are case reports or small case series, not controlled studies. Substantial visual improvement might be a natural course of ION related to hypotension. We believe that the presenting case is anterior ION related to orthostatic hypotension and anemia, considering the numerous clinical settings and features.

We believe that the temporary ischemic insult by temporary hypoperfusion and underlying anemia is a major causative mechanism of the case. Impaired autoregulation of vessels supplying the optic nerve head might be a further contributing mechanism, as in cases of anterior ION resulting from rapid correction of malignant hypertension. Impaired autoregulation is also thought to be one of the causative mechanisms of conventional AION [18]. The reduced fluctuation in systemic blood pressure over a long period might have caused blunting of the autoregulatory reflex.

Tamsulosin is a α1-blocker, which is reported to be associated with orthostatic hypotension that results from an impaired compensatory reflex. The compensatory reflex mechanism mediated by the sympathetic nervous system is normally brought into effect when standing [21]. Therefore, this might be an additional contributing factor to the orthostatic hypotension in this case.

Prolonged bed rest may cause deep vein thrombosis and resultant pulmonary embolism. In rare case of paradoxical embolism, venous thrombi may cause arterial thrombosis. However, in the present case, there was no evidence of deep vein thrombosis, lateral opening of the heart, or arterial embolic phenomenon. Therefore, we do not consider deep vein thrombosis as a possible cause of the optic neuropathy.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.