Myiasis is infestation of a vertebrate with feeding fly larvae (Oestrus ovis); this affliction is most often limited to the external structures of the eye and is named external ophthalmomyiasis. When the larvae infest and feed on the structures of the eye, the condition is termed ophthalmomyiasis [1]. Catarrhal conjunctivitis is the most commonly reported case of conjunctivitis in the literature. Oestrus ovis infestation has been documented by six reports that describe 14 cases of Oestrus ovis ophthalmomyiasis externa. All cases had conjunctival injection, along with foreign body sensation; nine cases mentioned periorbital lid edema, and in two cases, there was follicular conjunctival reaction. Pseudomembrane formation was seen in one case [2,3]. A single case mentioned stromal keratitis along with subepithelial linear opacities and uveitis [3]. Management consists of topical lignocaine instillation, and liquid paraffin and 10% ethylether in vegetable oil can be used to anaesthetize and asphyxiate the larvae before removing them with fine forceps [4]. The most common cause of external ocular myiasis is infection with the larvae of the sheep botfly, Oestrus ovis [5]. The prevalence of ocular myiasis remains unknown in Southern Khorasan. This is the first report of frequency of corneal infiltration caused by Oestrus ovis infestation in the Southern region of Khorassan.

Materials

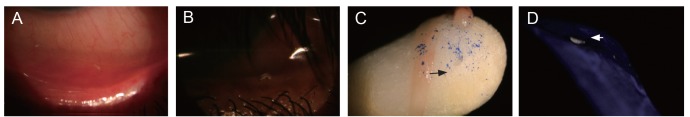

All patients referring to the emergency department of the main general hospital with red eye during the year 2011 were enrolled in this study. Ophthalmic biomicroscopic examination was performed to assess for abnormalities of the anterior segment. The clinical findings were recorded in a questionnaire sheet that was prepared for this reason. An external ophthalmomyiasis diagnosis was made according to clinical findings (foreign body sensation, lids edema, conjunctival congestion and watering eye, chimosis, and ruppy pattern discharge) and the presence of Oestrus ovis larvae. The larvae are transparent, segmented and have black mouthparts in the anterior region. Topical anesthetic drops were used to remove the larva with a plain fine forceps, and topical steroid and antibiotic drops were prescribed for five days thereafter.

Results

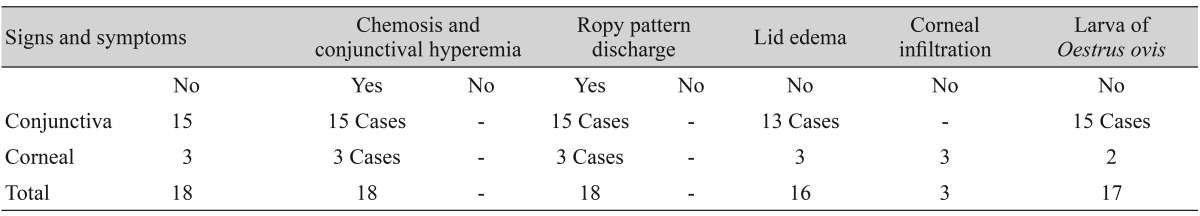

The frequency of external ophthalmomyiasis in Valiaser Hospital's emergency department during the year 2011 was 18 cases (Table 1). All the cases occurred in males who had jobs as farmers or who lived in a rural area. The patients ranged in age from 15 to 80 years.

All cases included a history of traveling to desert places or an environment with sheep six to 24 hours earlier, and all patients reported something striking their eye. Most patients had the signs of allergic conjunctivitis shown in Table 1, including conjunctival injection along with foreign body sensation, ropy pattern discharge, chemosis, periorbital lid edema, pseudomembrane and corneal infiltration. There was not a remarkable change in visual acuity during or after removal of the larvae.

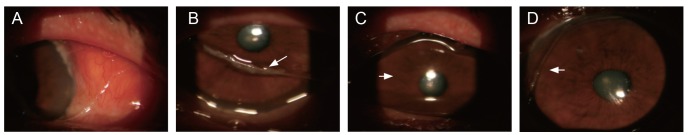

Three cases (75-, 59-, and 60-year-old residents) from rural areas referred to the emergency department at Valiaser Hospital reported that their foreign body sensation began immediately after exposure, and that tap water irrigation of their eyes did not relieve the discomfort. Overnight they experienced lid edema, epiphora, and the sensation that the foreign body was moving around their eye. The patients were referred to the hospital the next afternoon due to ocular discomfort. The visual acuity did not change much, with a clear central cornea without intraocular inflammation. The clear central area of the cornea is shown in Fig. 2.

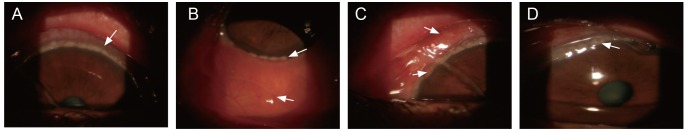

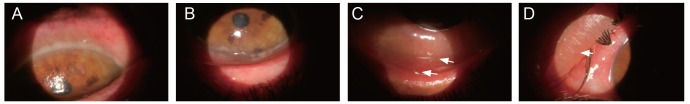

The visual acuity among these three cases with peripheral corneal involvement ranged from 20 / 20 to 20 / 30 in both eyes. Slit-lamp examination revealed chemosis, a ropy pattern discharge and corneal infiltration. After initial treatment, one patient no longer experienced the sensation of a moving foreign body; however, the other patients' symptoms and signs were not relived after two days of treatment (Figs. 1 and 2). No larva was found on the external surface of eyeball due to late referral in one case, but the external ophthalmomyiasis was characteristic. Figs. 3 and 4 showed the larva in the eye of one patient and corneal involvement in the other two cases. Topical betamthason and antibiotics were prescribed every eight hours for the next five days.

Discussion

The clinical presentation of external ophthalmomyasis is similar to viral or allergic conjunctivitis, with tearing, itching, hyperemia, and foreign-body sensation. Keratouveitis has been reported after conjunctivitis; however, there are a few cases of corneal involvement consisting of diffuse corneal edema, linear subepithelial corneal opacities and endothelial keratic precipitates [6,7]. This survey is the first ophthalmomyiasis report in the eastern area of Iran that was associated with well-defined signs such as red eye, conjunctival chemosis, and a ropy pattern discharge. Circumlimbal coronary-shape corneal infiltration is the specific finding in this report that we were not able to find in previous literature, except for a similar finding on conjunctiva as a gelatinous superior limbal conjunctival elevation with overlying fine white plaques (Tanas dots) in vernal limbitis [8].

The other finding of our study is the frequency and similarity of unilateral conjunctivitis without intraocular involvement as described by Masoodi and Hosseini [9] from the Fars Province in southern Iran. The symptoms began while the affected individual was outdoors during the daytime, after the sense of something striking their eye. None of the patients had a history of allergic reactions. Also, the first symptoms of foreign body sensation and itching in the eye appeared abruptly in all cases, unlikely related to other possible insults or causes. However, whether these corneal involvements are a result of direct mechanical insult or a toxic reaction is still uncertain and requires future study. If it has spread to the interior of the eye (ophthalmomyiasis interna), the resulting uveitis and endophthalmitis may require aggressive treatment such as vitrectomy and intra vitreal instillation of antibiotics, especially in cases where the visual prognosis remains poor [4,10,11].

This report encourages ophthalmologists to suspect external ophthalmomyiasis in people living outdoors and in rural places. The high frequency of external ophthalmomyiasis without intraocular involvement was another interesting finding of our study. The most probable reason that larvae did not invade the intraocular space in this survey may be related to early access to the medical department for the removal of larva. The other possible hypothesis is that this lack of intraocular involvement could be due to the type of masques or number of larval infestations.

A coronary pattern of corneal infiltration is the first report of an additional clinical finding in external ophthalmomyiasis, especially in patients with a history of an object striking the eye and in patients who reside in a rural location. Awareness of ophthalmomyiasis amongst ophthalmologists working in rural areas is important for the timely diagnosis and treatment of this infestation. A thorough examination of the eye under magnification and prompt removal of the larvae could obviate the disastrous complications of internal ophthalmomyiasis. Limiting the exposure to adult flies and exterminating the flies will play a major role in preventing the disease.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print