Regression of Iris Neovascularization after Subconjunctival Injection of Bevacizumab

Article information

Abstract

To describe three cases of neovascular glaucoma (NVG) where iris or angle neovascularization regressed remarkably after subconjunctival bevacizumab injections used as the initial treatment before pan retinal photocoagulation (PRP) and/or filtering surgery. Three consecutive NVG patients whose intraocular pressure (IOP) was not controlled with maximal medication were offered an off-label subconjunctival injection of bevacizumab (2.5-3.75 mg/0.1-0.15 mL, Avastin). Bevacizumab was injected into the subconjunctival space close to the corneal limbus in two or three quadrants using a 26-gauge needle. Serial anterior segment photographs were taken before and after the injection. Following subconjunctival injection of bevacizumab, iris or angle neovascularization regressed rapidly within several days. Such regression was accompanied by lowering of IOP in all three cases. The patients underwent subsequent PRP and/or filtering surgery, and the IOP was further stabilized. Our cases demonstrate that subconjunctival bevacizumab injection can be potentially useful as an initial treatment in NVG patients before laser or surgical treatment.

Recent studies have shown that intravitreal [1-6] or intracameral [7,8] injections of bevacizumab may be a useful adjunct for the treatment of neovascular glaucoma (NVG). Such injections resulted in a rapid regression of iris and angle neovascularization and the stabilization of intraocular pressure (IOP). However, the intraocular intervention needed to deliver this macromolecular agent is associated with risk of infectious endophthalmitis, vitreous hemorrhage, and retinal detachment [9-11]. Furthermore, intravitreal injections may be complicated by further IOP elevation in patients with NVG [12].

Recently, our group demonstrated that bevacizumab may be delivered to the anterior chamber by subconjunctival injection in rabbit eyes [13]. The present study describes three cases of NVG where iris or angle neovascularization has been successfully treated with a subconjunctival bevacizumab injection as the initial maneuver before pan retinal photocoagulation (PRP) and/or filtering surgery.

Case Reports

Case 1

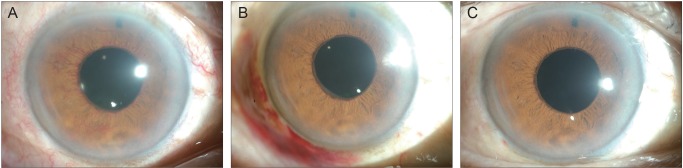

A 62-year-old male presented with decreased visual acuity in his right eye. He was diagnosed with proliferative diabetic retinopathy with concurrent NVG. The best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20 / 200, OD and 20 / 63, OS. IOPs were 45 mmHg, OD and 14 mmHg, OS, with maximally tolerated medical treatment (topical brimonidine, topical dorzolamide/timolol fixed combination [DTFC], and oral acetazolamide [250 mg, three times a day]). Slit lamp examination revealed active neovascularization in the right eye (Fig. 1A). The patient was offered a subconjunctival injection of bevacizumab (Avastin; Genentech Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) in the right eye. A total of 2.5 mg/0.1 mL of bevacizumab was injected at two locations (7 and 9 o'clock, approximately 1.25 mg/0.05 mL each) using a 26-gauge needle. After the injection, a noticeable bleb was produced. Two days after the injection, the IOP in the right eye was decreased to 21 mmHg. Slit lamp examination revealed a substantial regression of previously visible iris neovascularizations (Fig. 1B). On the fourth day after the bevacizumab injections, the IOP in the right eye was 23 mmHg. A remarkable regression of neovascularization was visible. The patient was further treated with three sessions of PRP. Two months after the bevacizumab injections, new vessels were not observed in either the iris or the angle (Fig. 1C). However, the IOP was 28 mmHg in the right eye with medication, and Ahmed glaucoma implant surgery was subsequently performed. Two months after the surgery, the IOP was controlled at 12 mmHg without any IOP-lowering medication.

Serial anterior segment photographs of the right eye of case 1. (A) Before subconjunctival injection of bevacizumab. Note the vigorous iris neovascularization. (B) Two days after injection. Iris neovascularization has much decreased. (C) Two months after injection. The new vessels are almost invisible.

Case 2

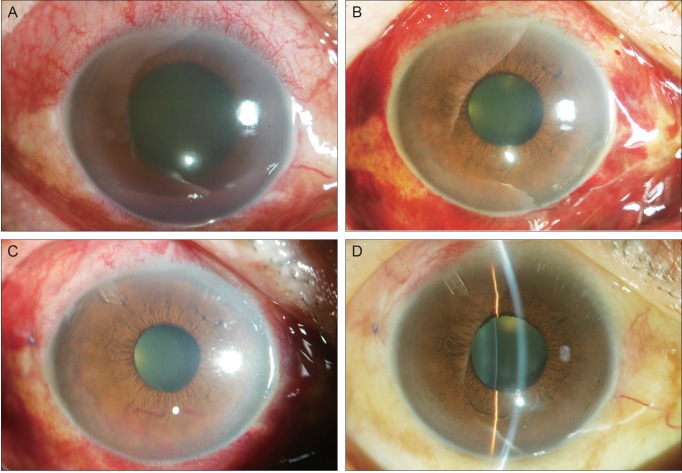

A 63-year-old male who had been diagnosed with central retinal vein occlusion in the right eye visited the emergency room with ocular pain and decreased visual acuity. He had been using topical DTFC and brimonidine twice a day for three months because of the IOP elevation after intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonid to control the macular edema. With medication, the IOP, OD had been controlled below 20 mmHg for three months. At the time of the emergency room visit, the patient's vision was hand movement, and the IOP was 48 mmHg in the right eye. Slit lamp examination of the right eye disclosed corneal edema and gross hyphema. Iris neovascularization was suspected in the inferior iris although it could not be confirmed due to corneal edema (Fig. 2A). Vitreous hemorrhage was also noted in the B-scan ultrasonograph. Subconjunctival injections, 3.75 mg/0.15 mL in total, were completed at the 5, 8, and 11 o'clock areas. One day later, IOP, OD decreased to 32 mmHg, and the cornea was much clearer. Two days after the injections, iris neovascularization was observed only on the margin of the pupil (Fig. 2B). The IOP, OD was 29 mmHg.

Serial anterior segment photographs of case 2. (A) Corneal edema and hyphema of the right eye is present on presentation. Iris neovascularization is suspected in the inferior iris although the view is limited due to corneal edema. (B) Clarity of the cornea increased two days after subconjunctival bevacizumab injection. (C) One day after drainage implant surgery and five days after subconjunctival injection. Vigorous iris neovascularization is visible on the inferior iris. (D) Three weeks after drainage implant surgery and second injection. No neovascularization was visible on the iris.

With the conditions much more amicable for surgery, Ahmed glaucoma implant surgery was performed on the right eye on the fourth day after the subconjunctival injections. Preoperative IOP, OD was consistently 29 mmHg. Although the IOP was decreased to 15 mmHg at the next surgery, vigorous iris neovascularization was noted in the inferior iris (Fig. 2C). Repeat subconjunctival injections of bevacizumab (1.25 mg/0.05 mL) were performed on this day. Five days after the second injection, the iris neovascularization disappeared completely. Three sessions of PRP were performed during the next three weeks. Three weeks after surgery, the IOP, OD was 17 mmHg, and no neovascularization was visible on the iris (Fig. 2D).

Case 3

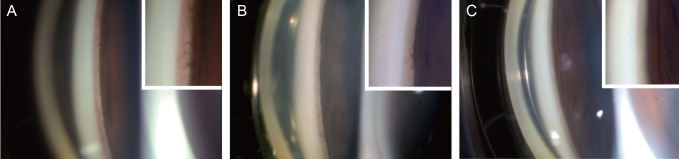

A 39-year-old male with type I diabetes, who had been previously diagnosed with bilateral proliferative diabetic retinopathy associated with NVG in his left eye, presented with visual disturbance in the left eye. Ophthalmic examination showed a BCVA of 20 / 25, OD, and 20 / 32, OS. The IOP was 11 mmHg, OD and 38 mmHg, OS despite treatment with both topical DTFC and brimonidine twice a day in the left eye. Slit lamp examination revealed neovascularization of the iris at the pupillary margin and neovascularization of the inferior, nasal, and temporal anterior chamber angle in the left eye (Fig. 3A). A subconjunctival injection of bevacizumab (2.5 mg/0.1 mL) was performed in the left eye. In the following days after the injection, a significant regression of the neovascularization was observed in the angle (Fig. 3B and 3C), and the IOP, OS was decreased to 19 mmHg. The patient was further treated with three sessions of PRP. Three months later, the IOP, OS was maintained at 14 mmHg with no neovascularizations visible in either the iris or angle.

Serial gonio photographs and magnified views of the angle (insets) of case 3. (A) Before subconjunctival injection of bevacizumab. Significant new vessels are present at the angle. (B) One day post-subconjunctival injection, regressing new vessel in the anterior chamber angle is notable. (C) Five days post-injection. New vessels are not present in the angle.

Discussion

We reported on three eyes with NVG where iris or angle neovascularization regressed rapidly after subconjunctival injections of bevacizumab with accompanying IOP reduction. Regression of the iris or angle neovascularization allowed for successful Ahmed glaucoma implant surgery, which might have otherwise been complicated with intraoperative and postoperative intracameral bleeding.

Recently, intravitreal [1-6] or intracameral [7,8] injections of bevacizumab have emerged as a new option in the treatment of NVG. They resulted in a rapid regression of the iris and angle neovascularization, which impeded the progression of peripheral anterior synechia in the period before the effect of PRP occurs. However, intravitreal and intracameral injections could be associated with the risk of infectious endophthalmitis, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, and further IOP elevation [9-11]. Subconjunctiv al injections are advantageous in that they are relatively free of these complications. This method is now often used for the treatment of corneal neovascularization or to reduce corneal graft rejection [14,15].

Since subconjucntival bevacizumab injections for NVG are yet to be a widely practiced procedure, there is no established standardized amount of bevacizumab that is recommended for each injection. However, bevacizumab is frequently introduced intravitreally. The most widely accepted amount of intravitreal bevacizumab is 1.25 mg/0.05 mL. A number of reports have demonstrated a dramatic therapeutic effect of this agent with this particular concentration [16-19]. Since we focused on the difference in the route of entry (intravitreal vs. subconjunctival), and not the minimal effective volume of the drug, the same amount known to be effective for intravitreal injections was used in this study. When 0.05 mL was injected, an injection bleb was created near the limbus across the 2 o'clock hour width. An amount greater than 0.05 mL expanded the bleb to the posterior direction, which was speculated not to have an additional effect in dispersing the bevacizumab into the anterior chamber or the iris.

We injected the bevacizumab at the near-limbal location which was close to the neovascularization of the iris (NVI). This was based on findings from a previous study. It has been suggested that macromolecules may diffuse through the sclera and directly into the iris after subconjunctival injections [20]. Therefore, in eyes with massive NVI distributed in wide regions of the iris, multiple injections of bevacizumab were performed. In eyes with localized, small degrees of NVI, bevacizumab was injected at one location near the limbus.

In pharmacokinetic studies, bevacizumab was detectable in the anterior chamber until one week after subconjunctival injections [13,21,22]. Therefore, its effect in suppressing anterior segment neovascularization should be transient. Nonetheless, our cases show that it is still useful in preventing the aggravation of the disease during the time window before applying further treatment such as PRP and filtering surgery. Moreover, associated IOP-lowering and decrease of hyphema, or corneal edema allows for prompt PRP. The regression of iris or angle neovascularization also results in conditions that are much more amicable for surgery.

In conclusion, our cases demonstrate that subconjunctival bevacizumab injections can be potentially useful for treatment of NVG as an initial treatment before PRP and/or filtering surgery. This maneuver may be particularly effective in patients presenting with high IOP or vigorous iris vascularization where intravitreal or intracameral injections of bevacizumab may be complicated by further IOP elevation. A large scale study is required to confirm the results found in this study.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital research fund.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.