If acute onset of esotropia is comitant, its cause is generally thought to be benign and further neurological investigationis not warranted.1,2 However, several reports3-7 have described patients with intracranial tumors who present with comitant esotropia and that the onset of comitant esotropia without any other neurological sings and symptoms in a child can be the first sign of a brain tumor. We describe a 3-year-old boy with acute comitant esotropia associated with a cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma in the absence of other neurological findings. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in Korea of acute comitant esotropia associated with a brain tumor.

Case Report

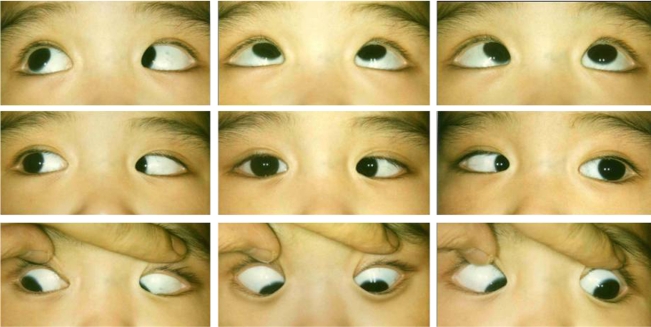

A 3-year-old boy was referred for management of acute acquired comitant esotropia. His family noticed sudden inward deviation of his left eye 9 months ago, and as time passed, this deviation became increasingly noticeable. On first presentation, the angle of esodeviation was 50 prism diopters (PD) at distant and near fixation. The patient's visual acuity and sensory status were not checked, but he demonstrated alternate fixation. There was no lateral incomitance and no deficit of abduction bilaterally (Fig. 1). No difference in the size of the deviation was found with fixation of the right versus the left eye. The cycloplegic refraction with 1% cyclopentolate revealed +0.75 diopters in both eyes. Very mild bilateral papilledema was found on fundus examination. No nystagmus was noticed, and there was no family history of strabismus or amblyopia. There was no preceding trauma or febrile illness before the onset of acute strabismus. Review of old photographs demonstrated that at 1 year of age, the patient's corneal light reflexes were centered.

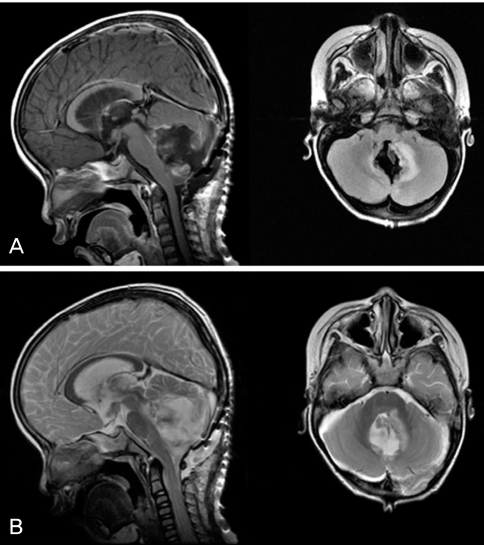

He was referred to a pediatric neurologist, but the neurological examination did not reveal any additional pathological findings. A brain MRI revealed a 5 cm mass with an enhanced peripheral rim at the midline of the cerebellum as well as hydrocephalus (Fig. 2). The tumor was completely excised and a shunt was placed. Histological examination of the excision confirmed the diagnosis of pilocytic astrocytoma.

Three months after neurosurgery the patient's visual acuity was 20/125 in each eye and the angle of esodeviaton increased up to 60PD at distance and near fixation without any deficit of abduction. Alternating six-hour occlusion therapy was initiated. Eight months after the initiation of occlusion therapy, the patient's visual acuity had improved to 20/50 in the right eye and 20/40 in the left eye. The angle of esodeviation was reduced to 50PD at distance and near fixation, and the esotropic angle did not show any sign of decrease.

One year after neurosurgery, a bilateral 6 mm recession of medial rectus muscles was performed. Immediately after the strabismus surgery, he was orthotropic at distant and near fixation. One month later, the angle of esodeviation became 10PD at distance and 6PD at near fixation. The visual acuity was 20/50 in the right eye and 20/40 in left eye. Occlusion therapy was stopped due to lack of patient compliance. At the last follow-up examination, 2 years after eye muscle surgery, the patient's angle of esodeviation remained 8PD at distant and near fixation (Fig. 3), and the corrected visual acuity was 20/40 with a glasses prescription of +0.75 diopters in both eyes. At this time, ocular motor fusion had not been reestablished following strabismus surgery.

Discussion

In most cases, the onset of acute acquired comitant esotropia occurs during infancy or childhood. Although comitancy is often thought to not be associated with neurologic disease,2 brain tumors and other intracranial processes in pediatric patients may in fact present with comitant esotropia.3-7 William and Hoyt5 described six children with acute onset of comitant esotropia who were found to have tumors of the brain stem or cerebellum. Several reports have established that brain tumors such as cerebellar astrocytomas,5-7 medulloblastomas,5 pontine gliomas,5 astrocytoma of the corpous callosum (with hydrocephalus),3 and Arnold Chiari malformation4,8 were associated with acute acquired comitant esotropia in childhood. Liu et al.9 reported 30 children with acquired esotropia resulting from known neurologic insults such as a brain tumor, meningitis, or pseudotumor cerebri. Of the 30 children reported, twelve (40%) of them had comitant esodeviation whereas the other 18 (60%) had incomitant esotropia. The authors concluded that comitant esodeviation can be common in children with identifiable neurologic insults.

The exact mechanism responsible for acute comitant esotropia in patients with brain tumors is not clear. Lennerstrand,10 Hoyt and Good11 reasoned that comitant strabismus might result from involvement of supranuclear mesencephalic structures, which control vergence eye movement. Jampolsky12 and others13,14 have ascribed acquired comitant esotropia to infranuclear insults, such as varying degrees of bilateral sixth nerve paresis. Spread of comitance is another suggested mechanism.15

The presenting clinical symptoms of patients with brain tumors are diverse, depending on the tumor's location and size, and sometimes, the age of the patient. Unlike various symptoms such as headache, vomiting, or more specific focal signs, acute comitant esotropia is a very unusual first sign of a brain tumor. Nevertheless, some authors have noted acute comitant esotropia as the first sign of a brain tumor.16-18 For example, Dikici et al.16 reported a 3-year-old boy presenting with acute comitant esotropia as the first sign of cerebellar astrocytoma, and the patient had no other neurologic signs or symptoms except moderate bilateral papilledema. Our case also presented with acute comitant esotropia as the first sign of cerebellar tumor, except our patient only had very mild bilateral papilledema. Zweifach17 presented the case of a 9-year-old boy with acute comitant esotropia in the absence of any neurologic symptoms or signs when first examined. Twenty eight months later, when he developed signs of posterior fossae dysfunction, he was found to have a cerebellar medulloblastoma. Musazadeh et al.18 also reported a 3-year-old boy with late onset esotropia without any neurologic signs and symptoms on first presentation. Eight months after first presentation, a brain MRI was performed to work-up the patient's intense headache, and imaging and biopsy revealed a cerebellar astrocytoma.

It is practically impossible to perform a radiologic examination of all children with isolated, acute comitant esotropia. No single clinical sign can reliably reveal the rare patient with acute onset of comitant esotropia secondary to a brain tumor. Lyons et al.19 have emphasized that a high index of clinical suspicion should be maintained, and a neuro-imaging study should be considered in the absence of expected findings associated with acute comitant esotropia such as hypermetropia, fusion potential, atypical features, or neurologic signs.

In conclusion, it is important to remember that acute comitant esotropia in the absence of other neurologic signs and symptoms in infancy or childhood may be the first sign of an underlying brain tumor.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print