|

|

| Korean J Ophthalmol > Volume 23(3); 2009 > Article |

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the visual outcomes and complications of unilateral scleral fixation of posterior chamber intraocular lenses (SF-PCIOLs) in pediatric complicated traumatic cataracts without capsular support.

Methods

This study involved five eyes of five children who underwent unilateral SF-PCIOL. All patients had a unilateral complicated traumatic cataract associated with anterior or posterior segment injury. Visual acuity (VA), IOL position, and postoperative complications were assessed during follow-up.

Results

The mean age of patients at the time of SF-PCIOL was 90 months (range, 66-115). The mean duration of follow-up time after surgery was 22 months (range, 5-55). In all patients, the best-corrected VA was either improved or was stable at last follow-up following SF-PCIOL implantation. There were no serious complications.

Following a unilateral traumatic cataract without adequate capsular support in children, the decision of optimal optical correction methods is challenging to ophthalmologists. As there is a risk of amblyopia in these patients, rapid optical and visual rehabilitation is very important. Nonsurgical methods with spectacles or contact lenses and surgical methods such as scleral fixation of posterior chamber intraocular lenses (SF-PCIOLs) may also be considered. Unilateral aphakic glasses are generally not suitable for children due to aniseikonia, which may impair binocularity. Contact lenses may cause corneal problems and poor compliance in pediatric patients as well as amblyopia, due to intermittent correction of refractive error.1 Also, in traumatized eyes, wearing contact lenses may be intolerable or difficult due to irregular corneal surfaces or conjunctival scarring from the trauma or multiple operations.

In the absence of adequate capsular support, an intraocular lens(IOL) cannot be inserted into the lens capsular bag and SF-PCIOL may be considered. Several reports indicated that SF-PCIOLs can be a safe and effective modality for the correction of aphakia in children.2,3 Here, authors evaluated whether unilateral SF-PCIOLs are also useful in pediatric complicated traumatic cataract cases.

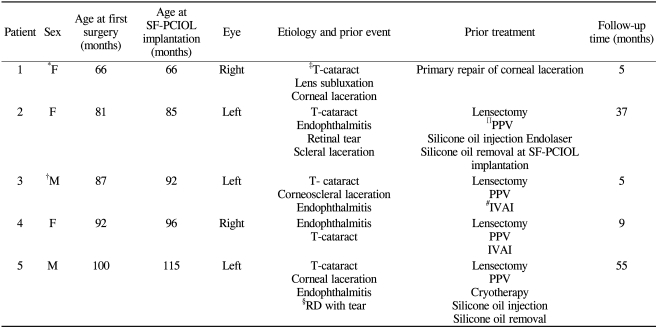

Five eyes of five patients (two males and three girls) undergoing unilateral SF-PCIOL from January 1999 to June 2007 at our hospital were retrospectively assessed. All children had a traumatic cataract and four children had endophthalmitis at the time of lens removal. One patient underwent IOL implantation at the time of pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) due to inadequate capsular support from a traumatic lens subluxation, while four patients underwent the SF-PCIOL as a secondary operation following primary PPV with lensectomy.

The mean age at the timeof initial lens removal was 85┬▒13 months (range, 66-100), and the mean age at the time of SF-PCIOL was 90┬▒18.0 months (range, 66-115).

All children had detailed preoperative and postoperative evaluations, including the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), refraction, measurement of intraocular pressure (IOP), slitlamp examination, and funduscopy. Each intraocular lens power was calculated using the SRK II formula. The postoperative refraction was targeted for emmetropia to +1.5D according to the children's age and their axial length. In patients where it was impossible to measure axial length or use keratometry, data from the opposite eye was used.

All patients underwent total PPV prior to or simultaneous with the SF-PCIOL. A superior conjunctival incision was made, extending approximately 180 degrees. SF-PCIOL was performed following total PPV using a double-armed 10-0 polypropylene curved suture needle. The suture needle was passed through the sclera approximately 1 mm posterior to the limbus and directed across the vitreous cavity toward a 26-gauge needle, which was also inserted through the sclera 1 mm posterior to the limbus 180 degrees opposite to the suture needle. The suture needle was then threaded into the 26-gauge needle barrel, and both were withdrawn through the 26-gauge needle entrance site. An 8 mm groove incision was made superiorly at the limbus. The polypropylene suture transversing the pupil was hooked and withdrawn through the superior corneoscleral incision site. The suture was cut, and the each cutting end was passed through the each haptic eyelet of a PCIOL and tied to the lens. An Alcon CZ70BD PMMA intraocular lens with a 7 mm diameter optic was used in all patients (Alcon, Fort Worth, Texas, USA). The prolene sutures were tightened and the lens was placed into the sulcus. The sutures were temporarily tied and the lens position was inspected. If the lens was adequately secured and correctly positioned, the sutures were tied permanently. The groove incision was closed using interrupted 10-0 nylon sutures. Subconjunctival injection of 0.25 mL of dexamethasone, 4 mg/mL, and gentamycin, 20 mg/mL, were given. Antibiotic ointment was applied, and the eye was patched and shielded.

Clinical characteristics of the patients are noted in Table 1. The mean age at the time of SF-PCIOL was 90┬▒18 months (range, 66-115). All patients had aunilateral traumatic cataract associated with anterior or posterior segment injury. Four patients had been subjected to prior PPV and lensectomy and the SF-PCIOL was performed as a secondary procedure. One patient had a SF-PCIOL at the time of PPV and lensectomy due toinadequate capsular support from traumatic lens subluxation. The mean follow-up time after SF-PCIOL was 22 months (range, 5-55).

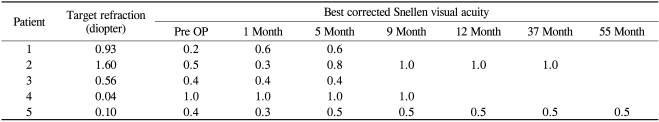

The preoperative and final visual acuities were compared and summarized in Table 2. Compared to baseline, all patients had either an improved or stable BCVA at last follow-up. Two of five patients (40%) improved their final postoperative best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) by more than two Snellen lines. From one month after SF-PCIOL, three of five patients (60%) had a BCVA that was continuously the same as their final BCVA. The preoperative and final BCVA were both 0.4 in one case. This result was thought to be due to a linear central corneal opacity in the patient, affecting the patient's visual axis.

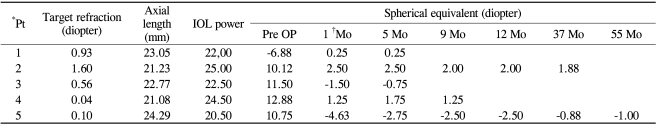

Each target refraction was designed preoperatively from plano to +1.60 diopters depending on the patient's age and axial length. A summary of the refractive results for all patients is shown in Tables 3 and 4. During follow-up, the actual refraction (spherical equivalent) and the difference between the actual refraction and the target refraction decreased in all five patients. The mean difference of the final refraction and target refraction was 0.91┬▒0.43 diopters (range 0.28-1.31 diopters), which was not statistically significant (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, p=0.50). Three of five patients (60%) had postoperative refractions at one month after SF-PCIOL that were within 1.25 diopters of the target refraction. In four of five patients (80%), each spherical equivalent at one month after operation was within 0.75 diopters of the final spherical equivalent. From one month after SF-PCIOL, four of five patients (80%) had refractions were stable within 0.75 diopters of range.

After operation, four (80%) patients had a centric stable IOL position with no IOL-related complications. In one case, IOL optic capture was discovered three days after operationand IOL repositioning was performed. Pilocarpine was prescribed and the patient was discharged. No further surgical interventions were necessary in this case. IOL optic capture did not affect the patient's spherical equivalent values. There were no cases of IOL dislocation due to suture breakage or slippage during follow-up.

In one case, the IOP measured 30 mmHg on the day after surgery. Cosopt® and Alphagan® were prescribed twice a day for one day and the IOP decreased to 13 mmHg within twenty-four hours. In all other cases, the preoperative and postoperative IOP values were within normal limits.

Our results in visual acuity changes are similar to previous studies4-13 which have reported either good visual preservation or improvement following SF-PCIOL in children. Most of these reported cases were primary implantations, while all of our cases were complicated traumatic cataracts with four cases having secondary IOL implantations. Therefore, our results may differ from results of operations for simple lens dislocation or subluxation. In the current study, all patients had either an improved or stable BCVA following SF-PCIOL. Two of five patients (40%) improved their final postoperative best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) by more than two Snellen lines. These results suggest the possibility that SF-PCIOL may be a useful treatment for pediatric, complicated,traumatic cataracts. Three of five patients (60%) had BCVAs that were the same as their final BCVA from one month following the operation. This suggests that vision may be stable in the early postoperative period. In one case, both the preoperative and postoperative BCVA was 0.4. This result was thought to be related to previous central scarring and opacification of the cornea, caused by trauma. There have been previous studies reporting decreased postoperative visual outcomes due to corneal pathologies.13

Refractive changes following IOL implantation in infants and children is difficult to predict accurately. When choosing a lens diopter for children, changes in the axial length should be considered. If the targeted refraction goal is emmetropia, amblyopia treatment will be easier but may result in myopia later in life. If the target refraction goal is hyperopia, amblyopia treatment may be more difficult, but emmetropia later in life is more likely.14 Awner et al., and Buckley et al., advocated a postoperative refraction of +2.0D for children four to six years old, +1.0D for those six to eight years old, and emmetropia in children over eight years old, adjusting for the fellow eye to avoid anisometropia greater than 3.00D.15,16

In this study, the target refraction ranged from plano to +1.6 diopters depending on the patient's age and axial length. Three of five patients (60%) had postoperative refractions at one month following operation that were within 1.25 diopters of the target refraction. In four of five patients (80%), the spherical equivalent at one month following operation was within 0.75 diopters of the final spherical equivalent and thereafter their refractions were also stable to within 0.75 diopters of range, suggesting that refractive values following SF-PCIOL may be generally stable in the early postoperative stage.

During follow-up, the difference between the actual refraction and the target refraction decreased in all five cases regardless of whether the refractive values one month following operation were myopic or hyperopic as compared to the target refraction.

SF-PCIOL in a vitrectomized eye may allow a greater tilt of the IOL. There is a particular risk of pupillary capture of the IOL optic.3 In one case, IOL capture was found on the third postoperative day and IOL repositioning was performed. IOL capture can usually be reversed, either spontaneously or with the use of mydriatic drops and supine positioning. The probability of pupil capture diminishes with time postoperatively.17

There was one case where the IOP increased to 30 mmHg on the first post-operative day. Following administration of IOP lowering agents, the IOP normalized in twenty-four hours. There were no cases of uncontrolled postoperative IOP.

Spontaneous breakage of the polypropylene suture leads to IOL displacement.18,19 There were no cases of polypropylene suture breakage in the current study.

To maintain the proper positioning of the IOL for an extended periodof time, tight suture fixation, correct sulcus positioning, and the residual capsule play an important role.20 Polypropylene sutures are generally considered to be long-lasting, but eventually may biodegrade and do not necessarily provide permanent IOL fixation.21,22 To reduce suture breakage, multiple sutures may be applied on both haptics and the use of different suture materials may be considered.21

There were no cases of postoperative limitation of extraocular movement, all patients demonstrated orthophoria.

Late endophthalmitis following SF-PCIOL has been reported in the literature,10,23,24 though none occurred in this study. Retinal detachment has been reported to occur following SF-PCIOL.4-13 This may be related to meticulous removal of the vitreous before IOL implantation.25 Retinal detachment did not occur in this study.

This study is limited by the small sample size and limited follow-up period. There were various surgeries that included not only SF-PCIOL but also pars plana vitrectomy (PPV), silicone oil tamponade and removal, among others. These other surgeries led to difficulty in interpretation of the postoperative results. However, SF-PCIOL was performed after identification and stabilization from previous surgeries, such as PPV or silicone oil removal, in four patients and from primary corneal repair in one patient. Nevertheless, there is a possibility that these surgeries may have biased the study results. Further studies with an increased size and longer follow-up are needed.

Because pediatric traumatic cataracts without adequate capsular support are usually unilateral and associated with morphological changes of the orb, such as corneal flattening or surface irregularity, SF-PCIOL may be superior to contact lenses for visual correction in these patients. In conclusion, despite the above limitations, our study demonstrated that unilateral SF-PCIOL implantation may be a safe and effective treatment for pediatric, complicated, traumatic cataracts.

Notes

The concept of this paper was presented as a poster at the 100th annual meeting of the Korean Ophthalmological Society, November, 2008.

REFERENCES

2. Buckley EG. Hanging by a thread: The long term efficacy and safety of transscleral sutured intraocular lenses in children (An American ophthalmological society thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2007;105:294-311.

3. Johnston RL, Charteris DG, Horgan SE, Cooling RJ. Combined pars plana vitrectomy and sutured posterior chamber implant. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:905-910.

4. Sharpe MR, Biglan AW, Gerontis CC. Scleral fixation of posterior chamber intraocular lenses in children. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 1996;27:337-341.

5. Lam DS, Ng JS, Fan DS, et al. Short term results of scleral intraocular lens fixation in children. J Cataract Refract Surg 1998;24:1474-1479.

6. Kumar M, Arora R, Sanga L, Sota LD. Scleral-fixated intraocular lens implantation in unilateral aphakic children. Ophthalmology 1999;106:2184-2189.

7. Zetterstrom C, Lundvall A, Weeber H Jr, Jeeves M. Sulcus fixation without capsular support in children. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25:776-781.

8. Buckley EG. Scleral fixated (sutured) posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation in children. J AAPOS 1999;3:289-294.

9. Jacobi PC, Dietlein TS, Jacobi FK. Scleral fixation of secondary foldable multifocal intraocular lens implants in children and young adults. Ophthalmology 2002;109:2315-2324.

10. Ozmen AT, Dogru M, Erturk H, Ozcetin H. Transsclerally fixated intraocular lenses in children. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 2002;33:394-399.

11. Sewelam A. Four-point fixation of posterior chamber intraocular lenses in children with unilateral aphakia. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:294-300.

12. Bardorf CM, Epley KD, Lueder GT, Tychsen L. Pediatric transscleral sutured intraocular lenses: efficacy and safety in 43 eyes followed an average of 3 years. J AAPOS 2004;8:318-324.

13. Asadi R, Kheirkhah A. Long-term results of scleral fixation of posterior chamber intraocular lenses in children. Ophthalmology 2008;115:67-72.

14. Maya ET, Steven M, Archer SM, et al. Intraocular lens power calculation in children. Ophthalmol 2007;52:474-482.

15. Awner S, Buckley EG, DeVaro JM, Seaber JH. Unilateral pseudophakia in children under 4 years. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1996;33:230-236.

16. Buckley EG, Klomberg LA, Seaber JH, et al. Management of the posterior capsule during pediatric intraocular lens implantation. Am J Ophthalmol 1993;115:722-728.

17. Johnston RL, Charteris DG. Pars plana vitrectomy and sutured posterior chamber lens implantation. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2001;12:216-221.

18. Vote BJ, Tranos P, Bunce C, et al. Long-term outcome of combined pars plana vitrectomy and scleral fixated sutured posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;41:308-312.

19. Assia EI, Nemet A, Sachs D. Bilateral spontaneous subluxation of scleral-fixated intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:2214-2216.

20. McCluskey P, Harrisberg B. Long-term results using scleral-fixated posterior chamber intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg 1994;20:34-39.

21. Altman AJ, Gorn RA, Craft J, Albert DM. The breakdown of polypropylene in the human eye: is it clinically significant? Ann Ophthalmol 1986;18:182-185.

22. Jongebloed WL, Worst JF. Degradation of polypropylene in the human eye: a SEM-study. Doc Ophthalmol 1986;64:143-152.

23. Kocak-Altintas AG, Kacak-Midillioglu I, Dengisik F, Duman S. Implantation of scleral-sutured posterior chamber intraocular lenses during penetrating keratoplasty. J Refract Surg 2000;16:456-458.

24. Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, Feuer W. Endophthalmitis after secondary intraocular lens implantation. A case-report study. Ophthalmology 1995;102:1925-1931.

25. Ashraf MF, Stark WJ, McCannel . In: Azar DT, Sutures and secondary iris fixated intraocular lenses. Intraocular Lenses in Cataract and Refractive Surgery. 2001. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; chap. 7.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print