New Korean Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Dry Eye Disease

Article information

Abstract

New Korean guidelines for the diagnosis and management of dry eye disease were developed based on literature reviews by the Korean Dry Eye Guideline Establishment Committee, a previous dry eye guideline by Korean Corneal Disease Study Group, a survey of Korean Dry Eye Society (KDES) members, and KDES consensus meetings. The new definition of dry eye was also proposed by KDES regular members. The new definition by the regular members of the KDES is as follows: “Dry eye is a disease of the ocular surface characterized by tear film abnormalities and ocular symptoms.” The combination of ocular symptoms and an unstable tear film (tear breakup time <7 seconds) was considered as essential components for the diagnosis of dry eye. Schirmer test and ocular surface staining were considered adjunctive diagnostic criteria. The treatment guidelines consisted of a simplified stepwise approach according to aqueous deficiency dominant, evaporation dominant, and altered tear distribution subtypes. New Korean guidelines can be used as a simple, valid, and accessible tool for the diagnosis and management of dry eye disease in clinical practice.

Introduction

Dry eye has historically been thought to be due to inadequate tear production or impaired tear film stability. In 1995, the National Eye Institute/Industry Workshop defined dry eye as follows: “Dry eye is a disorder of the tear film due to lack of tears or excessive evaporation that causes damage to the interpalpebral ocular surface and is associated with symptoms of ocular discomfort” [1]. It is noteworthy that this definition used the term “disorder” rather than “disease.” In 2006, the Delphi panel proposed a new term for dry eye disease (DED) as “dysfunctional tear syndrome (DTS),” and a diagnosis of severity based on symptoms and signs [2]. In 2007, a consensus for dry eye was made at the Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) supported by the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS). The first TFOS DEWS definition was as follows: “Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that results in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance, and tear film instability with potential damage to the ocular surface. It is accompanied by increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface” [3]. The original TFOS DEWS was the first to address that dry eye was a disease entity, not a disorder [3]. The Delphi panel [2] and the TFOS DEWS [4] recommended treatment guidelines based on severity level of dry eye. In 2017, the definition of dry eye in TFOS DEWS II was determined as follows: “ Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles” [5]. The etiologic classification of DED consisted of the two predominant and nonmutually exclusive categories; aqueous-deficient dry eye (ADDE) and evaporative dry eye in TFOS DEWS II [5]. Additionally, staged management was suggested rather than severity-based management of dry eye [6]. Meanwhile, Asia Dry Eye Society (ADES) emphasized the importance of tear film instability in dry eye and in 2017 defined dry eye as follows: “Dry eye is a multifactorial disease characterized by unstable tear film causing a variety of symptoms and/or visual impairment, potentially accompanied by ocular surface damage” [7]. ADES also reported dry eye classification based on target tear components (aqueous tears, lipid layer, secretory mucin, and membrane-associated mucin) and recommended tear film-oriented therapy [7,8].

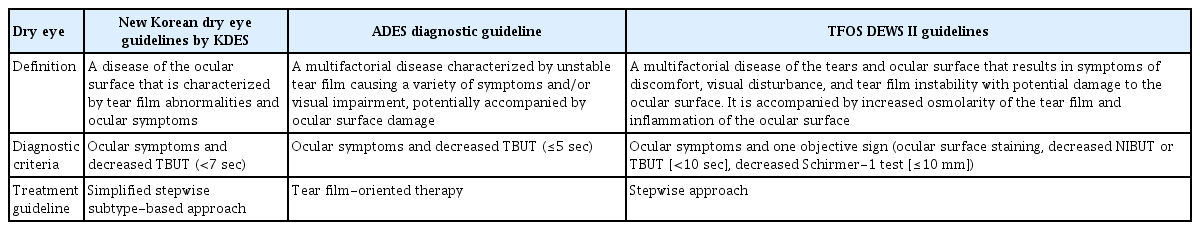

Clinical guidelines for dry eye in South Korea were first established in 2014 [9]. Korean Corneal Disease Study Group (KCDSG) published guidelines for the diagnosis according to the symptoms and signs of dry eye based on the severity (levels I–IV) and recommended treatment methods according to the level (Tables 1, 2) [9]. The Korean Dry Eye Society (KDES) was founded in August 2016 to contribute to dry eye research, international academic interaction, and public education and awareness, and 60 regular members were initially elected among Korean cornea specialists in 2017. Since the establishment of the first Korean dry eye guidelines [9], the extensive revision of the existing guidelines has become necessary due to changes in dry eye treatment patterns, the release of new treatment drugs, various diagnostic devices, and insurance issues.

Treatment recommendations according to the severity level of dry eye disease by the Korean Corneal Disease Study Group

The purpose of this study was to present concise and intuitive clinical guidelines for dry eye for Korean ophthalmologists. The Korean Dry Eye Guideline Establishment Committee (DHK, YE, CHY, HSL, HSH, JHK, TK, JSS, and KCY) in KDES developed the new dry eye guidelines based on literature reviews, a survey of KDES members, and KDES consensus meetings.

Proposed New Definition of Dry Eye

DED was defined in a previous Korean guideline as “a disease of the ocular surface that is associated with tear film abnormalities” [9]. The concise definition, mention of symptoms, and addition of the ocular surface and tear film were derived from face-to-face discussions between regular members of KDES. The final consensus meeting was held in Busan, Korea, on February 11, 2023, and the new definition agreed upon by the regular members of the KDES is as follows: “Dry eye is a disease of the ocular surface characterized by tear film abnormalities and ocular symptoms.” Ocular symptoms include dryness, discomfort, foreign body sensation, pain, blurring, and visual fluctuation [9]. KDES members agreed that ocular surface inflammation and tear film instability are major contributors to dry eye. In addition, tear hyperosmolarity was agreed to be an important element in the pathogenesis of DED. Respondents from KDES members indicated that tear film instability (58%) and ocular surface inflammation (36%) were perceived as the most important causes of dry eye. Tear film abnormalities included tear film instability due to evaporation and aqueous deficiency and altered tear distribution due to various abnormal anatomical changes around the ocular surface.

Proposed Diagnosis of Dry Eye

The practical diagnostic guideline for dry eye according to the new definition was discussed at the consensus meetings in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2023. All KDES members agreed that a dry eye patient should be diagnosed if he or she has at least one symptom and one objective sign. Fluorescein tear breakup time (TBUT), Schirmer test, and ocular surface staining were the most commonly performed tests to diagnose dry eye in the KDES member survey. The members responded that TBUT was the most important finding in tear film instability among TBUT, noninvasive TBUT (NIBUT), and tear breakup patterns. In the TFOS DEWS II diagnostic test battery, NIBUT <10 seconds is included as a diagnostic criterion, and TBUT can be used only when NIBUT is not available [10]. ADES sets the criterion for unstable tear film as TBUT ≤5 seconds [7]. Meanwhile, the multinational Ocular Dryness Disease Severity (ODISSEY) European Consensus Group established a practical algorithm for severe dry eye in 2014 [11]. Ocular symptoms (Ocular Surface Disease Index ≥33) and ocular surface staining (corneal fluorescein staining ≥3) were primary diagnostic criteria [11]. The consensus among KDES members regarding the diagnosis of dry eye is as follows: (1) the cutoff value of TBUT needs to be adjusted in the range of 5 to 10 seconds; (2) Schirmer test <10 mm has low sensitivity; (3) the mixed form of ADDE and evaporative dry eye needs to be expressed; and (4) the subtype of altered tear such as lid abnormalities should be addressed. Additionally, the KDES member survey identified TBUT <7 seconds as the most appropriate criterion for tear film instability in South Korea. Fifty-five percent of all KDES members agreed that symptoms and TBUT (<7 seconds) should be included as essential criteria in the Korean dry eye guidelines, and Schirmer test and ocular surface staining a re considered as adjunctive criteria. Accordingly, a diagnostic battery as shown in Fig. 1 was determined. The combination of ocular symptoms and an unstable tear film (TBUT <7 seconds) is considered sufficient to make a diagnosis of dry eye. Decreased tear volume (Schirmer test <10 mm) and ocular surface staining were reported as secondary diagnostic factors (±). Based on the results of tear volume, TBUT, and tear distribution, dry eye subtypes are classified as aqueous deficiency dominant, evaporative dominant, and altered tear distribution in the new Korean dry eye guidelines (Fig. 1). Sjögren syndrome and meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD)-related dry eye are representative of the aqueous-deficient and evaporative-dominant subtypes, respectively (Fig. 1). Altered tear distribution subtype include lid abnormality, conjunctivochalasis, and abnormal blinking (Fig. 1). Although the TFOS DEWS II definition included corneal neuropathic pain [5,10], the KDES members decided to exclude neuropathic pain from the diagnosis of dry eye due to no objective sign. In addition, it was agreed that the following are appropriate as auxiliary elements of the Korean dry eye diagnosis guidelines: (1) dry eye symptom questionnaire; (2) strip meniscometry; (3) tear meniscometry using optical coherence or slit-lamp biomicroscope; (4) conjunctival impression cytology; (5) corneal sensitivity; (6) tear osmolarity; (7) tear matrix metalloproteinase-9 level; (8) tear film interferometry; and (9) meibography.

Proposed Treatment Guidelines for Dry Eye

Previous guidelines by the KCDSG presented treatment methods according to the level of severity [9]. Most of the KDES members mentioned that the previous guidelines were not appropriate for the recent clinical setting, as level 2 drugs were used preemptively in some of the level 1 patients, and sometimes level 3 treatments were used if necessary. KDES members agreed that it is appropriate to include the following as the Korean dry eye treatment guidelines: (1) education and environmental modifications; (2) elimination of offending medications; (3) artificial tears and ointment; (4) lipid-containing agent; (5) lid hygiene and warm compresses; (6) dietary modifications; (7) topical corticosteroids; (8) topical immunomodulatory drugs (cyclosporine A, etc.); (9) topical secretagogues (diquafosol, rebamipide, etc.); (10) dietary modifications; (11) blood derivatives (autologous serum, platelet-rich plasma, etc.); (12) therapeutic contact lens; (13) punctal occlusion; (14) moisture goggles; (15) surgical approaches; (16) thermal pulsation therapy (Lipiflow, iLux, etc.), and (17) intense pulsed light (IPL). In addition, there has been enough discussion about which of stepwise and subtype-based treatment would be appropriate, and how many steps would be appropriate. It was also mentioned that clinical procedures such as punctal occlusion and IPL should be classified separately from general steps. Forty-four percent of KDES members supported simplified stepwise subtype-based treatment guideline. The support rates for the four-step stepwise subtype-based treatment and the stepwise treatment without subtype discrimination were 34% and 18%, respectively. Accordingly, the Korean Dry Eye Guideline Establishment Committee established a two-step stepwise treatment guideline based on the new dry eye subtype, and the procedures were separately classified as shown in Fig. 2. The treatment guideline is simplified to step 1 or 2, and the subtype-based treatments are suggested for dry eye subtype in the new Korean dry eye diagnostic guideline. This guideline emphasizes various treatment options can be used initially, as needed.

Discussion

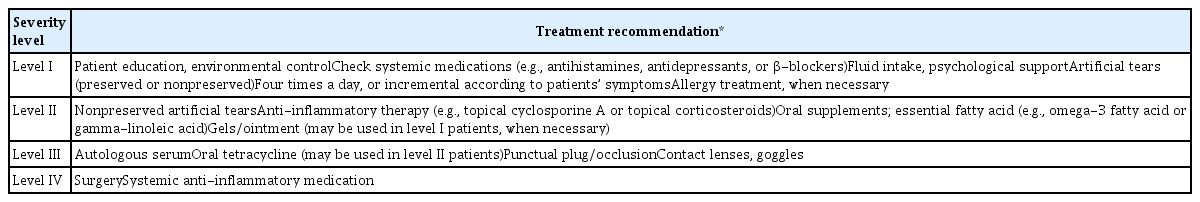

The new Korean guidelines for dry eye are simple, intuitive, and easy to use in clinical practice. Previous and contemporary evidence-based concepts in the diagnosis and management of dry eye were considered in developing these guidelines [1–11]. The new definition of dry eye by KDES is “Dry eye is a disease of the ocular surface characterized by tear film abnormalities and ocular symptoms.” Ocular symptoms and tear film instability (TBUT <7 seconds) are primary criteria in diagnosing dry eye, and Schirmer test and ocular surface staining are classified into auxiliary components. There are three subtypes of dry eye in this new guideline: (1) aqueous deficiency dominant; (2) evaporative dominant; and (3) altered tear distribution. These subtypes can cover all patients with dry eye except of corneal neuropathic pain. The new treatment guidelines are simplified to step 1 or 2 according to the subtypes of dry eye, and the clinical procedure has been separated. Table 3 compared KDES, ADES, and TFOS DEWS II clinical guidelines of dry eye. We think that the new Korean dry eye guidelines are simple, intuitive, understandable, and comprehensive compared to ADES and TFOS DEWS II guidelines.

Ocular symptoms and tear film instability are only included in the new Korean definition of dry eye. While the TFOS DEWS II and ADES definitions included the term “multifactorial,” the new Korean definition did not. Because many studies about dry eye have already shown that dry eye is a multifactorial disease and all KDES members already accept this as a matter of course, we did not used this term for concise expression [12–26]. Previously, ocular surface staining was considered an essential part of diagnosis [1,2]. However, ocular surface staining is not required for the definitive diagnosis of dry eye. In a previous Japanese clinical study, 76% of dry eye patients had a negative ocular surface staining, but 95% of them had an unstable tear film (TBUT ≤5 seconds) [7,27]. Retrospective medical records of 1,691 Korean patients with dry eye showed that 47.5% of them were level I with minimal ocular surface staining [9]. Eom et al.’s study [28] also demonstrated that 54.4% of 158 Korean patients with dry eye were also level I. Mean TBUT in patients with level I was 3.2 ± 1.5 seconds. Additionally, KDES members agreed that tear film abnormality is a term that could include the concepts of unstable tear film and altered tear distribution. Accordingly, ocular symptoms and tear film abnormalities are considered to be sufficient to constitute the definition of dry eye.

Previous diagnostic guidelines by the KCDSG were modified from the dry eye severity grading scheme of the DEWS [3], and ocular surface staining was weighted in grading the disease severity [9]. Ocular signs might include conjunctival injection, lid abnormalities (blepharitis, trichiasis, keratinization, and symblepharon), and tear film abnormalities (debris, decreased tear meniscus, and mucus clumping) [9]; however, these signs are not considered in the grading of dry eye in the previous Korean guideline. Since grading schemes were excluded from the new Korean guidelines, simple and clear diagnostic criteria were required. As mentioned above, there are many dry eye patients who demonstrate no ocular staining in Korea. There are wide intrapatient variations in the Schirmer-1 test, and the test is not routinely performed on every dry eye patient in the office [9]. Therefore, most KDES members agreed that TBUT was the most meaningful sign in dry eye. NIBUT, which is a diagnostic criterion in TFOS DEWS II, has a disadvantage because all Korean ophthalmologists cannot apply it. Fluorescein TBUT is the most widely used sign that can be easily checked in the office, although the variability in the volume of fluorescein or observer may affects TBUT. It is known that NIBUT was significantly longer than TBUT in patients with dry eye and the mean difference between NIBUT and TBUT was 2.0 seconds (95% confidence interval, 1.1–3.4 seconds) [29]. Therefore, TBUT <7 seconds is considered as the most appropriate diagnostic sign for dry eye in KDES member survey. The combination of ocular symptoms and TBUT <7 seconds is considered sufficient to cover overall dry eye patients in Korea. Meanwhile, the ADES guidelines classified dry eye as aqueous deficient, increased evaporation, and decreased wettability dry eye [13]. KDES members agreed that although decreased wettability may be an important factor in dry eye, a major drawback is that there is still no method to easily measure it in the clinical setting. It was also commented that the ADES diagnostic guidelines do not sufficiently include entities for altered tear distribution. Accordingly, KDES guidelines classified dry eye subtypes as aqueous deficiency dominant, evaporation dominant, and altered tear distribution.

TFOS DEWS II management reported that many treatment options for dry eye are poorly supported by level I studies [6]. Nevertheless, environmental and dietary modifications, elimination of offending factors, artificial tears, ointment, topical agents including corticosteroids, secretagogues, immunomodulators, and blood derivatives, lid hygiene, warm compress, punctal occlusion, IPL, and thermal pulsation therapy, etc., are helpful for dry eye patients [6,8,9,30]. Previous treatment guidelines by the KCDSG presented a stepladder approach according to severity level [9]. However, because of the heterogeneity in characteristics of dry eye patients, it is important for ophthalmologists to compound various treatments appropriately for individual dry eye patients. In the recent KDES consensus meetings, most KDES members favored a stepwise treatment guideline such as the TFOS DEWS II [6], but about half of the members supported the more simplified guidelines that take into account the subtypes of dry eye according to the new diagnostic guideline. In the clinical setting in Korea, the procedure can also be performed preemptively, so the procedural part is separated. Topical secretagogues such as diquafosol and rebamipide are not approved in the United States, making them clinically difficult to prescribe to dry eye patients. On the other hand, topical immunomodulators such as topical cyclosporine and lifitegrast are not approved in Japan. Both topical secretagogues and immunomodulators can be prescribed for dry eye patients only in South Korea. We believe that an immediate and effective treatment for dry eye patients can be achieved under the new simplified treatment guideline.

Conclusion

The new Korean dry eye guidelines can be used as a simple, valid, and accessible tool for the diagnosis and management of dry eye in clinical practice, even for general ophthalmologists. We are convinced that the guideline of this paper may be used as a basis for further discussions for the diagnosis and management of dry eye.

Acknowledgements

All members of the Korean Dry Eye Society who were not listed as authors, made valuable contributions to this study.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: The Korean Dry Eye Society is partially supported by Santen Pharmaceutical, but the sponsor had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Funding: None.