Uveitis with Hyphema Mimicking Infectious Endophthalmitis after Glaucoma Filtering Surgery: A Case Report

Article information

Dear Editor,

This report presents a case that, based on sclerotomy-site hyphema and inflammation, had been diagnosed as bleb-associated infectious endophthalmitis but was subsequently reassessed as an instance of uveitis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jeju National University Hospital (No. 2023-10-009) and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for publication of the research details and clinical images was obtained from the patient.

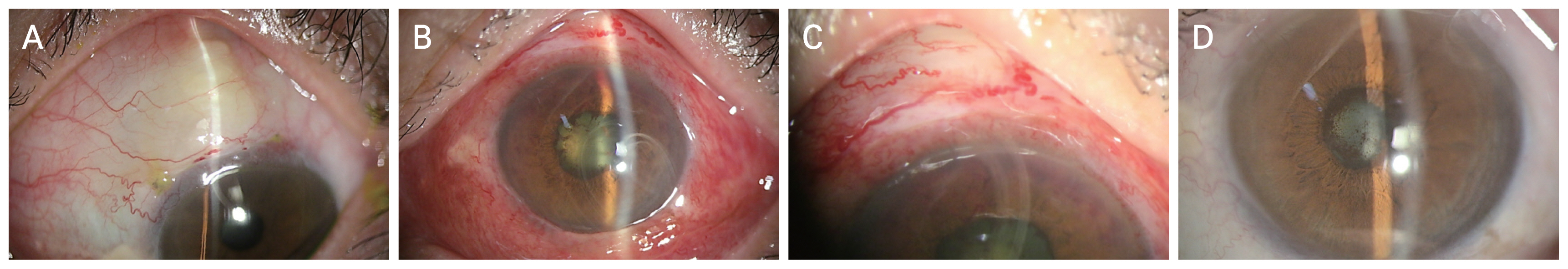

A Korean man in his 50s underwent an uncomplicated trabeculectomy for uncontrolled intraocular pressure (IOP) on the left eye due to primary open-angle glaucoma. The patient showed no signs of uveitis and had no previous history of intraocular inflammation. He had no medical history other than hypertension. The surgery proceeded as follows. A fornix-based conjunctival incision was performed; then, creating a 2.5 × 2.5-mm triangular, one-third-thickness scleral flap, mitomycin-C (0.2 mg/mL) was applied for 2.5 minutes. An internal sclerostomy was created with a Kelly glaucoma punch (19-gauge, 1.0 mm; Geuder AG). An iridectomy was performed, and the scleral flap was sutured by 1 bite of 10-0 nylon. A collagen matrix (Ologen) was inserted, and the conjunctival closing was performed via two limbal 9-0 Vicryl sutures (Ethicon). Following trabeculectomy, visual acuity (VA) was 20 / 25, and IOP was maintained between 8 and 10 mmHg without the use of ocular hypotensive medication (Fig. 1A).

Images of the patient. (A) Morphology of the bleb 1 month after the trabeculectomy. (B) Slit-lamp examination revealed the presence of 4+ cells with fibrin and blood clots in the anterior chamber, primarily concentrated around the previous sclerostomy site. The superior portion of the anterior chamber appears shallow, likely due to the presence of posterior synechiae, leading to the formation of focal iris bombe. (C) Bleb morphology during the occurrence of inflammation. (D) Accompanying severe posterior synechia and cataract due to waxing and waning inflammation.

Eight months postoperatively, the patient complained of several days’ severe pain and diminished VA in the operated eye. His VA dropped to hand-motion, and IOP was 22 mmHg. A slit-lamp examination showed diffuse severe conjunctival injection and corneal edema. The anterior chamber contained 4+ cells with fibrin and blood clots, mainly around the previous sclerostomy site (Fig. 1B, 1C).

Considering the possibility of bleb-associated infection, immediate bleb exploration, aqueous-humor sampling and a swab culture were performed. The previously inserted collagen matrix partially remained. The sclerostomy site was clear with minimal fibrosis. It was not sutured, as there was insufficient evidence that the surgical site was the source of inflammation. However, as it was not possible to rule out infection caused by other factors, intracameral antibiotics injection was performed.

Microbiological tests showed negative results for both bacteria and fungus. No findings suggestive of posterior segment inflammation were identified in the fundus image, optical coherence tomography, and fluorescein angiography. Nonocular imaging, such as chest and pelvis radiography, infectious testing (including polymerase chain reaction for cytomegalovirus, varicella zoster virus, herpes simplex virus), serology tests for Toxoplasma gondii and Toxocara canis, as well as rapid plasma reagin/treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay and interferon-γ release assay, all yielded negative results. Also, autoantibody testing, including antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor, as well as human leukocyte antigen testings, produced negative results. Thereafter, while treated with high-dose oral and topical prednisolone, the patient’s symptoms and inflammation improved. Due to waxing and waning uveitis, however, there were accompanying severe posterior synechia and cataract (Fig. 1D). Cataract extraction was performed, 6 months after which, VA was 20 / 25 and IOP was 11 mmHg without ocular hypotensive medication, and the patient did not exhibit a recurrence of uveitis with a low dose of topical steroids.

Spontaneous hyphema results from any number of causes, though as a complication of anterior uveitis, it is rarely encountered [1]. Previous reports have described hyphema with iritis cases manifesting with uveitic entities including rheumatoid arthritis, gout, erythema nodosum, gonococcal or herpes simplex infections, and/or Behçet disease; however, neither the nature nor incidence of this complication, not to mention outcomes, has as yet been clearly determined, owing to the lack of a sufficient number of uveitis-associated hemorrhage cases in the literature [2]. In our case, similarly, no systemic or ocular disease that might have caused the severe intraocular inflammation could be identified.

Despite advancements in surgical technology and the availability of new antibiotics, bleb-associated infection remains a serious and vision-threatening complication of trabeculectomy [3]. The typical clinical bleb findings are those associated with blebitis: mucopurulent infiltrate, resulting in a bleb of characteristic milky white color, accompanied by conjunctival congestion, epithelial defect, and/or bleb leakage [1]. One study on bleb-associated infection with a 32-patient series [4] found purulent bleb material in as many as 59% of cases. In this case, the likelihood of infection was low, as the intraoperative bleb examination revealed no signs of inflammatory infiltration or purulent material. However, it is important to consider the possibility that the Ologen implant may have functioned as a foreign antigen, triggering immune reactions [5].

Accurate differential diagnosis is crucial for distinct management in infectious and noninfectious inflammation. Ophthalmologists monitoring filtering blebs should carefully assess morphology for this differentiation.

Acknowledgements

None.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Funding: None.