Combined Cytomegalovirus and Herpes Simplex Virus-related Neuroretinitis in an Immunocompetent Patient

Article information

Dear Editor,

Neuroretinitis is optic nerve inflammation characterized by optic disc swelling and macular hard exudates in a starshaped pattern. It has been reported to be associated with a wide spectrum of infectious disease, such as cat-scratch disease, syphilis, and toxoplasmosis [1]. Neuroretinitis is an uncommon manifestation of cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections, and there have been no published case reports of combined CMV and HSV-related neuroretinitis. We report an unusual case of neuroretinitis in a healthy patient. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case.

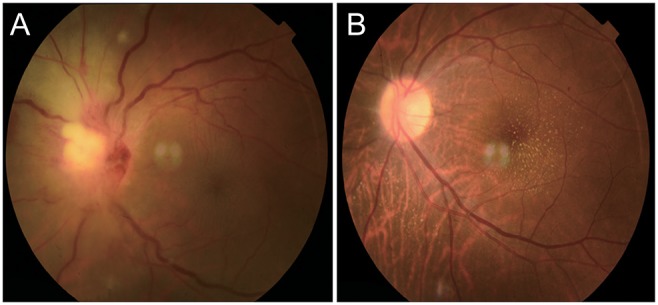

A 48-year-old healthy female presented with blurring of vision in the left eye for 3 days. She reported a 1-week history of flu-like symptoms. On physical examination, initial visual acuity was 20 / 20 in the right eye and 20 / 200 in the left eye. The intraocular pressure was normal in both eyes. Left ocular examination demonstrated grade 2 anterior chamber cells without iris atrophy. Both pupils were 3 mm in size, and relative afferent pupillary defect grade II was noted in the left eye. Fundus examination revealed optic disc swelling associated with retinitis at the superonasal part of the optic disc, and a segmental whitened area at the superonasal quadrant of the retina. The ocular findings were consistent with neuroretinitis and secondary branch retinal artery occlusion. Fundus fluorescein angiography showed delayed arterial filling at the superior-nasal branch of the retinal artery, a hyperfluorescent area consistent with leakage in the area of retinitis, and optic disc leakage. On laboratory evaluation, the complete blood count showed leukocytosis with lymphocyte predominance. The following laboratory analyses were unremarkable: blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, liver function test, anti-HIV antibody, hemoculture, venereal disease research laboratory, treponema pallidum haemagglutination, toxoplasmosis immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG, tuberculin skin test, chest X-ray, and urine analysis. Serological detection of Bartonella and the corresponding titer could not be performed at our hospital. Laboratory investigation of the immune status showed normal CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell counts. Serologic tests showed negative CMV IgM, positive CMV IgG, negative HSV IgM, and positive HSV IgG. Aqueous qualitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for viruses was performed. Contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed a hypersignal in the left optic nerve with gadolinium enhancement on the T2-weighted image. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis was normal. The patient received intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/day) for 3 days, followed by prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day. However, there was minimal improvement of disc swelling and macular edema. At 1 week, aqueous PCR results for HSV type I and CMV were positive. The sensitivity and specificity of PCR testing on ocular fluids were 80.9 % and 97.4%, respectively. There were no viral DNA copy numbers. After treatment, the patient's clinical features improved. Hence, we shifted our approach to antiviral treatment. Valganciclovir was not be administered because of financial issues. Intravenous ganciclovir 5 mg/kg every 12 hours was administered for 2 weeks, followed by intravitreal ganciclovir injection 2 mg/0.1 mL weekly for 4 weeks. Prednisolone was rapidly tapered during the ganciclovir course. At the 4-week follow-up, left visual acuity had improved to 20 / 50. In addition, the ocular examination showed resolution of inflammation and retinitis (Fig. 1A, 1B).

Fundus photograph taken (A) at first presentation compared with fundus photograph (B) at 8-week follow-up.

CMV neuroretinitis can be caused by primary infection of the optic nerve or secondary involvement through spread of the infection from adjacent areas of the retina [2]. HSV-related optic neuropathy can be caused by several mechanisms, including intraneural vasculitis, compressive ischemia of the optic nerve, and inflammation and necrosis due to direct herpes virus infection [3]. Concomitant ocular infection with CMV and HSV has been reported as endotheliitis in an immunocompetent patient [4]. However, there has been no case report on concomitant infection of CMV and HSV neuroretinitis in an immunocompetent patient. Intravenous ganciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir for induction and maintenance therapy are effective, but have major systemic side effects. Valganciclovir is another effective treatment with fewer major side effects, but it is expensive. Intravitreal injection of ganciclovir is an alternative effective local treatment with no systemic side effects [5]. Moreover, we use ganciclovir therapy because it acts against both CMV and HSV.

In conclusion, we report a case of infectious/parainfectious optic neuropathy that initially presented as papillitis and minimal retinitis and evolved into neuroretinitis. Viral infections, including those caused by HSV and CMV, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of neuroretinitis in immunocompetent patients. Proper investigations and treatment are essential to establish the etiology and achieve beneficial outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Tayakorn Kupakanjana, associated with the Department of Ophthalmology, Thammasat University Faculty of Medicine for his careful revision of the description of this study.

Notes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.